Bette Davis (Bette Davis)

Ruth Elizabeth Davis, known from early childhood as “Betty,” was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, at 55 Cedar Street, the daughter of Ruth Augusta “Ruthie” (née Favor), born in Tyngsboro, Massachusetts, and Harlow Morrell Davis, a law student born in Augusta, Maine. Her sister, Barbara Harriet “Bobby”, was born October 25, 1909 at 55 Ward Street in Somerville, Massachusetts, their father is now a patent attorney/lawyer. The family was Protestant, of English, French, and Welsh ancestry. In 1915, Davis’s parents separated and Betty and Bobby attended a Spartan boarding school called Crestalban in Lanesborough, which is located in the Berkshires. In 1921, Ruth Davis moved to New York City with her daughters, where she worked as a portrait photographer. Betty was inspired to become an actress after seeing Rudolph Valentino in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and Mary Pickford in Little Lord Fauntleroy (1921), and changed the spelling of her name to “Bette” after Honoré de Balzac’s La Cousine Bette. She received encouragement from her mother, who had aspired to become an actress. She attended Cushing Academy, a boarding school in Ashburnham, Massachusetts, where she met her future husband, Harmon O. Nelson, known as “Ham.” In 1926, she saw a production of Henrik Ibsen’s The Wild Duck with Blanche Yurka and Peg Entwistle. Davis later recalled that it inspired her full commitment to her chosen career, and said, “Before that performance I wanted to be an actress. When it ended, I had to be an actress … exactly like Peg Entwistle.” She auditioned for admission to Eva LeGallienne’s Manhattan Civic Repertory, but was rejected by LeGallienne who described her attitude as “insincere” and “frivolous.” She was accepted by the John Murray Anderson School of Theatre, and studied dance with Martha Graham. She auditioned for George Cukor’s stock theater company, and although he was not very impressed, he gave Davis her first paid acting assignment anyway—a one-week stint playing the part of a chorus girl in the play Broadway. She was later chosen to play Hedwig, the character she had seen Entwistle play, in The Wild Duck. After performing in Philadelphia, Washington and Boston, she made her Broadway debut in 1929 in Broken Dishes, and followed it with Solid South. A Universal Studios talent scout saw her perform and invited her to Hollywood for a screen test.

Accompanied by her mother, Davis traveled by train to Hollywood, arriving on December 13, 1930. She later recounted her surprise that nobody from the studio was there to meet her; a studio employee had waited for her, but left because he saw nobody who “looked like an actress.” She failed her first screen test but was used in several screen tests for other actors. In a 1971 interview with Dick Cavett, she related the experience with the observation, “I was the most Yankee-est, most modest virgin who ever walked the earth. They laid me on a couch, and I tested fifteen men … They all had to lie on top of me and give me a passionate kiss. Oh, I thought I would die. Just thought I would die.”[8] A second test was arranged for Davis, for the film A House Divided (1931). Hastily dressed in an ill-fitting costume with a low neckline, she was rebuffed by the director William Wyler, who loudly commented to the assembled crew, “What do you think of these dames who show their chests and think they can get jobs?” Carl Laemmle, the head of Universal Studios, considered terminating Davis’s employment, but cinematographer Karl Freund told him she had “lovely eyes” and would be suitable for The Bad Sister (1931), in which she subsequently made her film debut. Her nervousness was compounded when she overheard the Chief of Production, Carl Laemmle, Jr., comment to another executive that she had “about as much sex appeal as Slim Summerville,” one of the film’s co-stars. The film was not a success, and her next role in Seed (1931) was too brief to attract attention. Universal Studios renewed her contract for three months, and she appeared in a small role in Waterloo Bridge (1931) before being lent to Columbia Pictures for The Menace and to Capital Films for Hell’s House (all 1932). After nine months, and six unsuccessful films, Laemmle elected not to renew her contract. Davis was preparing to return to New York when actor George Arliss chose Davis for the lead female role in the Warner Brothers picture The Man Who Played God (1932), and for the rest of her life, Davis credited him with helping her achieve her “break” in Hollywood. The Saturday Evening Post wrote, “she is not only beautiful, but she bubbles with charm,” and compared her to Constance Bennett and Olive Borden. Warner Bros. signed her to a five-year contract, and she remained with the studio for the next eighteen years, garnering great acclaim for herself as well as making a fortune for her employers. In 1932, she married Harmon “Ham” Nelson, who was scrutinized by the press; his $100 a week earnings compared unfavorably with Davis’s reported $1,000 a week income. Davis addressed the issue in an interview, pointing out that many Hollywood wives earned more than their husbands, but the situation proved difficult for Nelson, who refused to allow Davis to purchase a house until he could afford to pay for it himself. Davis had several abortions during the marriage.

After more than 20 film roles, the role of the vicious and slatternly Mildred Rogers in the RKO Radio production of Of Human Bondage (1934), a film adaptation of W. Somerset Maugham’s novel, earned Davis her first major critical acclaim. Many actresses feared playing unsympathetic characters and several had refused the role, but Davis viewed it as an opportunity to show the range of her acting skills. Her co-star, Leslie Howard, was initially dismissive of her, but as filming progressed his attitude changed and he subsequently spoke highly of her abilities. The director, John Cromwell, allowed her relative freedom, and commented, “I let Bette have her head. I trusted her instincts.” She insisted that she be portrayed realistically in her death scene, and said, “the last stages of consumption, poverty and neglect are not pretty and I intended to be convincing-looking.” The film was a success, and Davis’s confronting characterization won praise from critics, with Life magazine writing that she gave “probably the best performance ever recorded on the screen by a U.S. actress.” Davis anticipated that her reception would encourage Warner Bros. to cast her in more important roles, and was disappointed when Jack Warner refused to lend her to Columbia Studios to appear in It Happened One Night, and instead cast her in the melodrama Housewife. When Davis was not nominated for an Academy Award for Of Human Bondage, The Hollywood Citizen News questioned the omission and Norma Shearer, herself a nominee, joined a campaign to have Davis nominated. This prompted an announcement from the Academy president, Howard Estabrook, who said that under the circumstances “any voter … may write on the ballot his or her personal choice for the winners,” thus allowing, for the only time in the Academy’s history, the consideration of a candidate not officially nominated for an award. Claudette Colbert won the award for It Happened One Night but the uproar led to a change in Academy voting procedures the following year, whereby nominations were determined by votes from all eligible members of a particular branch, rather than by a smaller committee, with results independently tabulated by the accounting firm Price Waterhouse. Davis appeared in Dangerous (1935) as a troubled actress and received very good reviews. E. Arnot Robertson wrote in Picture Post, “I think Bette Davis would probably have been burned as a witch if she had lived two or three hundred years ago. She gives the curious feeling of being charged with power which can find no ordinary outlet.” The New York Times hailed her as “becoming one of the most interesting of our screen actresses.” She won the Academy Award for Best Actress for the role, but commented it was belated recognition for Of Human Bondage, calling the award a “consolation prize.” For the rest of her life, Davis maintained that she gave the statue its familiar name of “Oscar” because its posterior resembled that of her husband, whose middle name was Oscar, although her claim has been disputed by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, among others. In her next film, The Petrified Forest (1936), Davis co-starred with Leslie Howard and Humphrey Bogart, but Bogart, in his first important role, received most of the critics’ praise. Davis appeared in several films over the next two years but most were poorly received.

Convinced that her career was being damaged by a succession of mediocre films, Davis accepted an offer in 1936 to appear in two films in Britain. Knowing that she was breaching her contract with Warner Bros., she fled to Canada to avoid legal papers being served upon her. Eventually, Davis brought her case to court in Britain, hoping to get out of her contract with Warner Bros. She later recalled the opening statement of the barrister, Sir Patrick Hastings, who represented Warner Bros. Hastings urged the court to “come to the conclusion that this is rather a naughty young lady and that what she wants is more money.” He mocked Davis’s description of her contract as “slavery” by stating, incorrectly, that she was being paid $1,350 per week. He remarked, “if anybody wants to put me into perpetual servitude on the basis of that remuneration, I shall prepare to consider it.” The British press offered little support to Davis, and portrayed her as overpaid and ungrateful. Davis explained her viewpoint to a journalist, saying “I knew that, if I continued to appear in any more mediocre pictures, I would have no career left worth fighting for.” Davis’s counsel presented her complaints—that she could be suspended without pay for refusing a part, with the period of suspension added to her contract, that she could be called upon to play any part within her abilities regardless of her personal beliefs, that she could be required to support a political party against her beliefs, and that her image and likeness could be displayed in any manner deemed applicable by the studio. Jack Warner testified, and was asked, “Whatever part you choose to call upon her to play, if she thinks she can play it, whether it is distasteful and cheap, she has to play it?” Warner replied, “Yes, she must play it.” The case, decided by Branson J. in the English High Court, was reported as Warner Bros. Studios Incorporated v. Nelson in [1937] 1 KB 209. Davis lost the case and returned to Hollywood, in debt and without income, to resume her career. Olivia de Havilland mounted a similar case in 1943 and won.

Davis began work on Marked Woman (1937), as a prostitute in a contemporary gangster drama inspired by the case of Lucky Luciano. For her performance in the film she was awarded the Volpi Cup at the 1937 Venice Film Festival. Her next picture was Jezebel (1938), and during production Davis entered a relationship with director William Wyler. She later described him as the “love of my life,” and said that making the film with him was “the time in my life of my most perfect happiness.” The film was a success, and Davis’ performance as a spoiled Southern belle earned her a second Academy Award, which led to speculation in the press that she would be chosen to play a similar character, Scarlett O’Hara, in Gone with the Wind. Davis expressed her desire to play Scarlett, and while David O. Selznick was conducting a search for the actress to play the role, a radio poll named her as the audience favorite. Warners offered her services to Selznick as part of a deal that also included Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland, but Selznick did not consider Davis as suitable, and rejected the offer, while Davis did not want Flynn cast as Rhett Butler. Jezebel marked the beginning of the most successful phase of Davis’ career, and over the next few years she was listed in the annual “Quigley Poll of the Top Ten Money Making Stars,” which was compiled from the votes of movie exhibitors throughout the U.S. for the stars that had generated the most revenue in their theaters over the previous year. In contrast to Davis’ success, her husband, Ham Nelson, had failed to establish a career for himself, and their relationship faltered. In 1938, Nelson obtained evidence that Davis was engaged in a sexual relationship with Howard Hughes and subsequently filed for divorce citing Davis’ “cruel and inhuman manner.”

She was emotional during the making of her next film, Dark Victory (1939), and considered abandoning it until the producer Hal B. Wallis convinced her to channel her despair into her acting. The film became one of the highest grossing films of the year, and the role of Judith Traherne brought her an Academy Award nomination. In later years, Davis cited this performance as her personal favorite. She appeared in three other box office hits in 1939, The Old Maid with Miriam Hopkins, Juarez with Paul Muni and The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex with Errol Flynn. The latter was her first color film and her only color film made during the height of her career. To play the elderly Elizabeth I of England, Davis shaved her hairline and eyebrows. During filming she was visited on the set by the actor Charles Laughton. She commented that she had a “nerve” playing a woman in her sixties, to which Laughton replied, “Never not dare to hang yourself. That’s the only way you grow in your profession. You must continually attempt things that you think are beyond you, or you get into a complete rut.” Recalling the episode many years later, Davis remarked that Laughton’s advice had influenced her throughout her career. By this time, Davis was Warner Bros.’ most profitable star, and she was given the most important of their female leading roles. Her image was considered with more care; although she continued to play character roles, she was often filmed in close-ups that emphasized her distinctive eyes. All This and Heaven Too (1940) was the most financially successful film of Davis’ career to that point, while The Letter (1940) was considered “one of the best pictures of the year” by The Hollywood Reporter, and Davis won admiration for her portrayal of an adulterous killer, a role originated by famed actress Katharine Cornell. During this time, she was in a relationship with her former costar George Brent, who proposed marriage. Davis refused, as she had met Arthur Farnsworth, a New England innkeeper. Davis and Farnsworth were married at Home Ranch, in Lake Montezuma, Arizona, in December 1940.

In January 1941, Davis became the first female president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences but antagonized the committee members with her brash manner and radical proposals. Faced with the disapproval and resistance of the committee, Davis resigned, and was succeeded by her predecessor Walter Wanger. Davis starred in three movies in 1941, the first being The Great Lie, opposite George Brent. It was a refreshingly different role for Davis, as she played a kind, sympathetic character. Brent tickled Davis during many of the film’s scenes, which allowed the audience, used to Davis’ strong-willed character, a rare glimpse of her succumbing to giggles and squirms. William Wyler directed Davis for the third time in Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes (RKO, 1941), but they clashed over the character of Regina Giddens. Taking a role originally played on stage by Tallulah Bankhead, Davis felt Bankhead’s original interpretation was appropriate and followed Hellman’s intent, but Wyler wanted her to soften the character. Davis refused to compromise. She received another Academy Award nomination for her performance, and never worked with Wyler again.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Davis spent the early months of 1942 selling war bonds. After Jack Warner criticized her tendency to cajole crowds into buying, she reminded him that her audiences responded most strongly to her “bitch” performances. She sold two million dollars worth of bonds in two days, as well as a picture of herself in Jezebel for $250,000. She also performed for black regiments as the only white member of an acting troupe formed by Hattie McDaniel, which included Lena Horne and Ethel Waters. At John Garfield’s suggestion of opening a servicemen’s club in Hollywood, Davis—with the aid of Warner, Cary Grant and Jule Styne—transformed an old nightclub into the Hollywood Canteen, which opened on October 3, 1942. Hollywood’s most important stars volunteered to entertain servicemen. Davis ensured that every night there would be a few important “names” for the visiting soldiers to meet. She appeared as herself in the film Hollywood Canteen (1944), which used the canteen as the setting for a fictional story. Davis later commented, “There are few accomplishments in my life that I am sincerely proud of. The Hollywood Canteen is one of them.” In 1980, she was awarded the Distinguished Civilian Service Medal, the United States Department of Defense’s highest civilian award, for her work with the Hollywood Canteen.

Davis showed little interest in the film Now, Voyager (1942) until Hal Wallis advised her that female audiences needed romantic dramas to distract them from the reality of their lives. It became one of the best known of her “women’s pictures.” In one of the film’s most imitated scenes, Paul Henreid lights two cigarettes as he stares into Davis’ eyes and passes one to her. Film reviewers complimented Davis on her performance, the National Board of Review commenting that she gave the film “a dignity not fully warranted by the script.” During the early 1940’s, several of Davis’ film choices were influenced by the war, such as Watch on the Rhine (1943), by Lillian Hellman, and Thank Your Lucky Stars (1943), a lighthearted all-star musical cavalcade, with each of the featured stars donating their fee to the Hollywood Canteen. Davis performed a novelty song, “They’re Either Too Young or Too Old,” which became a hit record after the film’s release. Old Acquaintance (1943) reunited her with Miriam Hopkins in a story of two old friends who deal with the tensions created when one of them becomes a successful novelist. Davis felt that Hopkins tried to upstage her throughout the film. Director Vincent Sherman recalled the intense competitiveness and animosity between the two actresses, and Davis often joked that she held back nothing in a scene in which she was required to shake Hopkins in a fit of anger. In August 1943, Davis’ husband, Arthur Farnsworth, collapsed while walking along a Hollywood street and died two days later. An autopsy revealed that his fall had been caused by a skull fracture he had suffered two weeks earlier. Davis testified before an inquest that she knew of no event that might have caused the injury. A finding of accidental death was reached. Highly distraught, Davis attempted to withdraw from her next film Mr. Skeffington (1944); but Jack Warner, who had halted production following Farnsworth’s death, convinced her to continue. Although she had gained a reputation for being forthright and demanding, her behavior during filming of Mr. Skeffington was erratic and out of character. She alienated Vincent Sherman by refusing to film certain scenes and insisting that some sets be rebuilt. She improvised dialogue, causing confusion among other actors, and infuriated the writer, Julius Epstein, who was called upon to rewrite scenes at her whim. Davis later explained her actions with the observation, “when I was most unhappy I lashed out rather than whined.” Some reviewers criticized Davis for the excess of her performance; James Agee wrote that she “demonstrates the horrors of egocentricity on a marathonic scale;” but despite the mixed reviews, she received another Academy Award nomination.

In 1983, after filming the pilot episode for the television series Hotel, Davis was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a mastectomy. Within two weeks of her surgery she suffered four strokes which caused paralysis in the left side of her face and in her left arm, and left her with slurred speech. She commenced a lengthy period of physical therapy and, aided by her personal assistant, Kathryn Sermak, gained partial recovery from the paralysis. During this time, her relationship with her daughter, B. D. Hyman, deteriorated when Hyman became a born-again Christian and attempted to persuade Davis to follow suit. With her health stable, she traveled to England to film the Agatha Christie mystery Murder with Mirrors (1985). Upon her return, she learned that Hyman had published a memoir, My Mother’s Keeper, in which she chronicled a difficult mother-daughter relationship and depicted scenes of Davis’ overbearing and drunken behavior. Several of Davis’ friends commented that Hyman’s depictions of events were not accurate; one said, “so much of the book is out of context.” Mike Wallace rebroadcast a 60 Minutes interview he had filmed with Hyman a few years earlier in which she commended Davis on her skills as a mother, and said that she had adopted many of Davis’ principles in raising her own children. Critics of Hyman noted that Davis had financially supported the Hyman family for several years and had recently saved them from losing their house. Despite the acrimony of their divorce years earlier, Gary Merrill also defended Davis. Interviewed by CNN, Merrill said that Hyman was motivated by “cruelty and greed.” Davis’ adopted son, Michael Merrill, ended contact with Hyman and refused to speak to her again, as did Davis, who also disinherited her.

In her second memoir, This ‘N That (1987), Davis wrote, “I am still recovering from the fact that a child of mine would write about me behind my back, to say nothing about the kind of book it is. I will never recover as completely from B.D.’s book as I have from the stroke. Both were shattering experiences.” Her memoir concluded with a letter to her daughter, in which she addressed her several times as “Hyman,” and described her actions as “a glaring lack of loyalty and thanks for the very privileged life I feel you have been given”. She concluded with a reference to the title of Hyman’s book, “If it refers to money, if my memory serves me right, I’ve been your keeper all these many years. I am continuing to do so, as my name has made your book about me a success.” Davis appeared in the television film As Summers Die (1986) and Lindsay Anderson’s film The Whales of August (1987), in which she played the blind sister of Lillian Gish. The film earned good reviews, with one critic writing, “Bette crawls across the screen like a testy old hornet on a windowpane, snarling, staggering, twitching—a symphony of misfired synapses.” Her last performance was the title role in Larry Cohen’s Wicked Stepmother (1989). By this time her health was failing, and after disagreements with Cohen she walked off the set. The script was rewritten to place more emphasis on Barbara Carrera’s character, and the reworked version was released after Davis’ death.

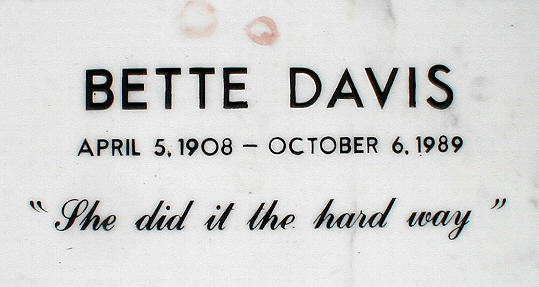

After abandoning Wicked Stepmother and with no further film offers (though she was keen to play the centenarian in Craig Calman’s The Turn Of The Century and worked with him on adapting the stage play to a feature length screenplay), Davis appeared on several talk shows and was interviewed by Johnny Carson, Joan Rivers, Larry King and David Letterman, discussing her career but refusing to discuss her daughter. Her appearances were popular; Lindsay Anderson observed that the public enjoyed seeing her behaving “so bitchy.” He commented, “I always disliked that because she was encouraged to behave badly. And I’d always hear her described by that awful word, feisty.” During 1988 and 1989, Davis was fêted for her career achievements, receiving the Kennedy Center Honor, the Legion of Honor from France, the Campione d’Italia from Italy and the Film Society of Lincoln Center Lifetime Achievement Award. She collapsed during the American Cinema Awards in 1989 and later discovered that her cancer had returned. She recovered sufficiently to travel to Spain where she was honored at the Donostia-San Sebastián International Film Festival, but during her visit her health rapidly deteriorated. Too weak to make the long journey back to the U.S., she traveled to France where she died on October 6, 1989, at 11:20 pm, at the American Hospital in Neuilly-sur-Seine. Davis was 81 years old. She was interred in Forest Lawn—Hollywood Hills Cemetery in Los Angeles, alongside her mother, Ruthie, and sister, Bobby, with her name in larger type size. On her tombstone is written: “She did it the hard way,” an epitaph that she mentioned in her memoir Mother Goddam as having been suggested to her by Joseph L. Mankiewicz shortly after they had filmed All About Eve.

Born

- April, 05, 1908

- USA

- Lowell, Massachusetts

Died

- October, 06, 1989

- Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

Cemetery

- Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Hollywood Hills)

- Los Angeles, California

- USA