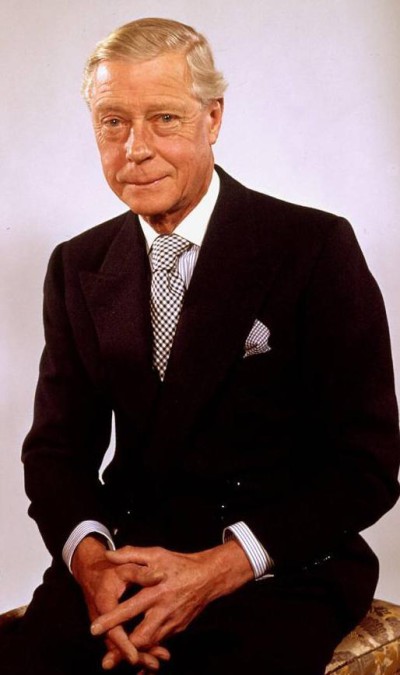

Edward VIII of the United Kingdom (Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David)

Edward VIII was born on 23 June 1894 at White Lodge, Richmond Park, on the outskirts of London, during the reign of his great-grandmother Queen Victoria. He was the eldest son of the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George V and Queen Mary). His father was the son of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra). His mother was the eldest daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Teck (Francis and Mary Adelaide). At the time of his birth, he was third in the line of succession to the throne, behind his grandfather and father. As a great-grandson of the monarch in the male line, Edward was styled His Highness Prince Edward of York at birth. He was baptised Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David in the Green Drawing Room of White Lodge on 16 July 1894 by Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury. The names were chosen in honour of Edward’s late uncle, who was known to his family as “Eddy” or Edward, and his great-grandfather King Christian IX of Denmark. The name Albert was included at the behest of Queen Victoria for her late husband Albert, Prince Consort, and the last four names – George, Andrew, Patrick and David – came from the Patron Saints of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. He was always known to his family and close friends by his last given name, David. Like other upper-class children of the time, Edward and his younger siblings were brought up by nannies rather than directly by their parents. One of his early nannies abused Edward by pinching him before he was due to be presented to his parents. His subsequent crying and wailing would lead the Duke and Duchess to send Edward and the nanny away. The nanny was subsequently discharged. Edward’s father, though a harsh disciplinarian, was demonstrably affectionate, and his mother displayed a frolicsome side with her children that belied her austere public image. She was amused by the children making tadpoles on toast for their French master, and encouraged them to confide in her.

Initially Edward was tutored at home by Helen Bricka. When his parents travelled the British Empire for almost nine months following the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, young Edward and his siblings stayed in Britain with their grandparents, Queen Alexandra and King Edward VII, who showered their grandchildren with affection. Upon his parents’ return, Edward was placed under the care of two men, Frederick Finch and Henry Hansell, who virtually brought up Edward and his brothers and sister for their remaining nursery years. Edward was kept under the strict tutorship of Hansell until nearly 13. He was taught German and French by private tutors. Edward took the examination to enter Osborne Naval College, and began there in 1907. Hansell had wanted Edward to enter school earlier, but his father disagreed. Following two years at Osborne College, which he did not enjoy, Edward moved on to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth. A course of two years followed by entry into the Royal Navy was planned. A bout of mumps may have left him sterile. When his father ascended the throne on 6 May 1910, following the death of Edward VII, Edward automatically became Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay, and he was created Prince of Wales a month later on 23 June 1910, his 16th birthday. Preparations began in earnest for his future duties as king. He was withdrawn from his naval course before his formal graduation, served as midshipman for three months aboard the battleship Hindustan, then immediately entered Magdalen College, Oxford, for which, in the opinion of his biographers, he was underprepared intellectually. A keen horseman, he learned how to play polo with the university club. He left Oxford after eight terms without any academic qualifications.

Edward was officially invested as Prince of Wales in a special ceremony at Caernarvon Castle on 13 July 1911. The investiture took place in Wales, at the instigation of the Welsh politician David Lloyd George, Constable of the Castle and Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Liberal government. Lloyd George invented a rather fanciful ceremony in the style of a Welsh pageant, and coached Edward to speak a few words in Welsh. When World War I (1914–18) broke out, Edward had reached the minimum age for active service and was keen to participate. He had joined the Grenadier Guards in June 1914, and although Edward was willing to serve on the front lines, Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener refused to allow it, citing the immense harm that would occur if the heir to the throne were captured by the enemy. Despite this, Edward witnessed trench warfare first-hand and attempted to visit the front line as often as he could, for which he was awarded the Military Cross in 1916. His role in the war, although limited, made him popular among veterans of the conflict. Edward undertook his first military flight in 1918, and later gained a pilot’s license. Throughout the 1920s, Edward, as Prince of Wales, represented his father, King George V, at home and abroad on many occasions. His rank, travels, good looks, and unmarried status gained him much public attention, and at the height of his popularity, he was the most photographed celebrity of his time. He took a particular interest in science and in 1926 was president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science when his alma mater, Oxford University, hosted the society’s annual general meeting. He also visited the poverty-stricken areas of the country, and undertook 16 tours to various parts of the Empire between 1919 and 1935. On a tour of Canada in 1919, he acquired the Bedingfield ranch, near Pekisko, Alberta, and in 1924, he donated the Prince of Wales Trophy to the National Hockey League. From January to April 1931, he and his brother, Prince George, travelled 18,000 miles on a tour of South America, voyaging out on the ocean liner Oropesa, and returning via Paris and an Imperial Airways flight from Paris–Le Bourget Airport that landed specially in Windsor Great Park. His attitudes towards many of the Empire’s subjects and various foreign peoples, both during his time as Prince of Wales and later as Duke of Windsor, were little commented upon at the time, but have soured his reputation subsequently. In 1920, he wrote of Indigenous Australians, “they are the most revolting form of living creatures I’ve ever seen!! They are the lowest known form of human beings & are the nearest thing to monkeys.”

Edward’s womanising and reckless behaviour during the 1920s and 1930s worried Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, King George V, and those close to the prince. Alan Lascelles, Edward’s private secretary for eight years during this period, believed that “for some hereditary or physiological reason his normal mental development stopped dead when he reached adolescence”. George V was disappointed by Edward’s failure to settle down in life, disgusted by his affairs with married women, and was reluctant to see him inherit the Crown. “After I am dead,” George said, “the boy will ruin himself in 12 months.” In 1929, Time magazine reported that Edward teased his sister-in-law, Elizabeth, the wife of his younger brother Albert, by calling her “Queen Elizabeth”. The magazine asked if “she did not sometimes wonder how much truth there is in the story that he once said he would renounce his rights upon the death of George V – which would make her nickname come true”. Edward’s brother and sister-in-law had two children, including Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Elizabeth II. George V favoured his son Albert (“Bertie”), and granddaughter Elizabeth (“Lilibet”), and told a courtier, “I pray to God that my eldest son [Edward] will never marry and have children, and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne.”

In 1930, George V gave Edward the lease of Fort Belvedere, in Windsor Great Park. There, Edward had relationships with a series of married women including textile heiress Freda Dudley Ward, and Lady Furness, the American wife of a British peer, who introduced the prince to her friend and fellow American Wallis Simpson. Simpson had divorced her first husband, U.S. naval officer Win Spencer, in 1927. Her second husband, Ernest Simpson, was a British-American businessman. Wallis Simpson and the Prince of Wales, it is generally accepted, became lovers while Lady Furness travelled abroad, though Edward adamantly insisted to his father that he was not intimate with her, and that it was not appropriate to describe her as his mistress. Edward’s relationship with Simpson, however, further weakened his poor relationship with his father. Although King George V and Queen Mary met Simpson at Buckingham Palace in 1935, they later refused to receive her. Edward’s affair with an American divorcee led to such grave concern that the couple were followed by members of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch, who examined in secret the nature of their relationship. An undated report detailed a visit by the couple to an antique shop, where the proprietor later noted “that the lady seemed to have POW [Prince of Wales] completely under her thumb.” The prospect of having an American divorcee with a questionable past having such sway over the heir apparent led to anxiety among government and establishment figures.

King George V died on 20 January 1936, and Edward ascended the throne as King Edward VIII. The next day, he broke royal protocol by watching the proclamation of his own accession from a window of St James’s Palace in the company of the then still-married Simpson. He became the first monarch of the British Empire to fly in an aircraft when he flew from Sandringham to London for his Accession Council. Edward caused unease in government circles with actions that were interpreted as interference in political matters. His comment during a tour of depressed villages in South Wales that “something must be done” for the unemployed coal miners was seen as directly critical of the Government, though it has never been clear whether Edward had anything in particular in mind. Government ministers were reluctant to send confidential documents and state papers to Fort Belvedere, because it was clear that Edward was paying little attention to them, and it was feared that Simpson and other house guests might read them, improperly or inadvertently disclosing information that could be detrimental to the national interest. Edward’s unorthodox approach to his role also extended to the currency which bore his image. He broke with the tradition that on coinage each successive monarch faced in the opposite direction to his or her predecessor. Edward insisted that he face left (as his father had done), to show the parting in his hair. Only a handful of test coins were struck before the abdication, and when George VI succeeded to the throne he also faced left, to maintain the tradition by suggesting that, had any coins been minted featuring Edward’s portrait, they would have shown him facing right.

On 16 July 1936, an Irish fraudster called Jerome Bannigan, alias George Andrew McMahon, produced a loaded revolver as Edward rode on horseback at Constitution Hill, near Buckingham Palace. Police spotted the gun and pounced on him; he was quickly arrested. At Bannigan’s trial, he alleged that “a foreign power” had approached him to kill Edward, that he had informed MI5 of the plan, and that he was merely seeing the plan through to help MI5 catch the real culprits. The court rejected the claims and sent him to jail for a year for “intent to alarm”. It is now thought that Bannigan had indeed been in contact with MI5, but the veracity of the remainder of his claims remains open. In August and September, Edward and Simpson cruised the Eastern Mediterranean on the steam yacht Nahlin. By October it was becoming clear that the new king planned to marry Simpson, especially when divorce proceedings between the Simpsons were brought at Ipswich Assizes. Preparations for all contingencies were made, including the prospect of the coronation of King Edward and Queen Wallis. Because of the religious implications of any marriage, plans were made to hold a secular coronation ceremony, not in the traditional religious location of Westminster Abbey, but in the Banqueting House in Whitehall. Although gossip about his affair was widespread in the United States, the British media kept voluntarily silent, and the public knew nothing until early December.

On 16 November 1936, Edward invited British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin to Buckingham Palace and expressed his desire to marry Wallis Simpson when she became free to remarry. Baldwin informed him that his subjects would deem the marriage morally unacceptable, largely because remarriage after divorce was opposed by the Church of England, and the people would not tolerate Wallis as queen. As king, Edward was the titular head of the Church of England, and the clergy expected him to support the Church’s teachings. Edward proposed an alternative solution of a morganatic marriage, in which he would remain king but Wallis would not become queen. She would enjoy some lesser title instead, and any children they might have would not inherit the throne. This too was rejected by the British Cabinet as well as other Dominion governments, whose views were sought pursuant to the Statute of Westminster 1931, which provided in part that “any alteration in the law touching the Succession to the Throne or the Royal Style and Titles shall hereafter require the assent as well of the Parliaments of all the Dominions as of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.” The Prime Ministers of Australia, Canada and South Africa made clear their opposition to the king marrying a divorcee; their Irish counterpart expressed indifference and detachment, while the Prime Minister of New Zealand, having never heard of Simpson before, vacillated in disbelief. Faced with this opposition, Edward at first responded that there were “not many people in Australia” and their opinion did not matter.

Edward informed Baldwin that he would abdicate if he could not marry Simpson. Baldwin then presented Edward with three choices: give up the idea of marriage; marry against his ministers’ wishes; or abdicate. It was clear that Edward was not prepared to give up Simpson, and he knew that if he married against the advice of his ministers, he would cause the government to resign, prompting a constitutional crisis. He chose to abdicate. Edward duly signed the instruments of abdication at Fort Belvedere on 10 December 1936 in the presence of his younger brothers: Prince Albert, Duke of York, next in line for the throne; Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester; and Prince George, Duke of Kent. The next day, the last act of his reign was the royal assent to His Majesty’s Declaration of Abdication Act 1936. As required by the Statute of Westminster, all the Dominions consented to the abdication. On the night of 11 December 1936, Edward, now reverted to the title and style of a prince, explained his decision to abdicate in a worldwide radio broadcast. He famously said, “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Edward departed Britain for Austria the following day; he was unable to join Simpson until her divorce became absolute, several months later. His brother, Prince Albert, Duke of York, succeeded to the throne as George VI. George VI’s elder daughter, Princess Elizabeth, became first in the line of succession, as heiress presumptive.

At the end of the war, the couple returned to France and spent the remainder of their lives essentially in retirement as the Duke never occupied another official role after his wartime governorship of the Bahamas. The Duke’s allowance was supplemented by government favours and illegal currency trading. The City of Paris provided the Duke with a house at 4 Route du Champ d’Entraînement, on the Neuilly-sur-Seine side of the Bois de Boulogne, for a nominal rent. The French government exempted him from paying income tax, and the couple were able to buy goods duty-free through the British embassy and the military commissary. In 1951, the Duke produced a ghost-written memoir, A King’s Story, in which he expresses disagreement with liberal politics. The royalties from the book added to their income. Nine years later, he penned a relatively unknown book, A Family Album, chiefly about the fashion and habits of the Royal Family throughout his life, from the time of Queen Victoria to that of his grandfather and father, and his own tastes.

The Duke and Duchess effectively took on the role of celebrities and were regarded as part of café society in the 1950s and 1960s. They hosted parties and shuttled between Paris and New York; Gore Vidal, who met the Windsors socially, reported on the vacuity of the Duke’s conversation. The couple doted on the pug dogs they kept. In June 1953, instead of attending the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in London, the Duke and Duchess watched the ceremony on television in Paris. The Duke said that it was contrary to precedent for a Sovereign or former Sovereign to attend any coronation of another. The Duke was paid to write articles on the ceremony for the Sunday Express and Woman’s Home Companion, as well as a short book, The Crown and the People, 1902–1953. In 1955, they visited President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the White House. The couple appeared on Edward R. Murrow’s television interview show Person to Person in 1956, and a 50-minute BBC television interview in 1970. That year, they were invited as guests of honour to a dinner at the White House by President Richard Nixon.

The Royal Family never fully accepted the Duchess. Queen Mary refused to receive her formally. However, the Duke sometimes met his mother and brother George VI, and attended George’s 1952 funeral. Queen Mary remained angry with Edward and indignant over his marriage to Wallis: “To give up all this for that”, she said. In 1965, the Duke and Duchess returned to London. They were visited by Elizabeth II, Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent, and Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood. A week later, the Princess Royal died, and they attended her memorial service. In 1967, they joined the Royal Family for the centenary of Queen Mary’s birth. The last royal ceremony the Duke attended was the funeral of Princess Marina in 1968. He declined an invitation from Elizabeth II to attend the investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969, replying that Prince Charles would not want his “aged great-uncle” there. In the 1960s, the Duke’s health deteriorated. In December 1964, he was operated on by Michael E. DeBakey in Houston for an aneurysm of the abdominal aorta, and in February 1965 a detached retina in his left eye was treated by Sir Stewart Duke-Elder. In late 1971, the Duke, who was a smoker from an early age, was diagnosed with throat cancer and underwent cobalt therapy. Queen Elizabeth II visited the Windsors in 1972 while on a state visit to France; however, only the Duchess appeared with the royal party for a photocall.

On 28 May 1972, the Duke died at his home in Paris, less than a month before his 78th birthday. His body was returned to Britain, lying in state at St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. The funeral service was held in the chapel on 5 June in the presence of the Queen, the Royal Family, and the Duchess of Windsor, who stayed at Buckingham Palace during her visit. The coffin was buried in the Royal Burial Ground behind the Royal Mausoleum of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Frogmore. Until a 1965 agreement with Queen Elizabeth II, the Duke and Duchess had previously planned for a burial in a purchased cemetery plot at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, where the father of the Duchess was interred. Frail, and suffering increasingly from dementia, the Duchess died 14 years later, and was buried alongside her husband as “Wallis, Duchess of Windsor”. In the view of historians such as Philip Williamson, the popular perception today that the abdication was driven by politics rather than religious morality is false, and arises because divorce has become much more common and socially acceptable, so to modern sensibilities the religious restrictions that prevented Edward continuing as king while married to Simpson “seem, wrongly, to provide insufficient explanation” for his abdication.

Born

- June, 23, 1894

- United Kingdom

- White Lodge, Richmond, Surrey

Died

- May, 28, 1972

- France

- Neuilly-sur-Seine, Paris

Cemetery

- Royal Burial Grounds at Frogmore

- Windsor, Berkshire, England

- United Kingdom