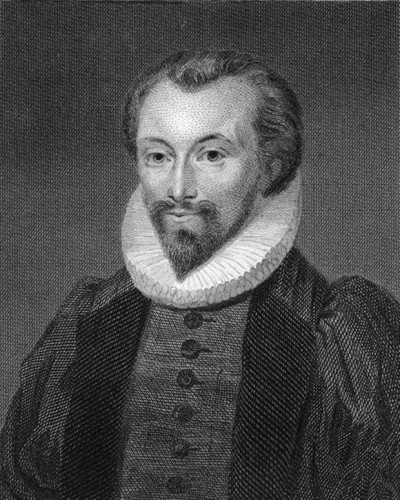

John Donne (John Donne)

Donne was born in London, into a recusant Roman Catholic family when practice of that religion was illegal in England. Donne was the third of six children. His father, also named John Donne, was of Welsh descent and a warden of the Ironmongers Company in the City of London. Donne’s father was a respected Roman Catholic who avoided unwelcome government attention out of fear of persecution. His father died in 1576, when Donne was four years old, leaving his son fatherless and his widow, Elizabeth Heywood, with the responsibility of raising their children alone. Heywood was also from a recusant Roman Catholic family, the daughter of John Heywood, the playwright, and sister of the Reverend Jasper Heywood, a Jesuit priest and translator. She was a great-niece of the Roman Catholic martyr Thomas More. This tradition of martyrdom would continue among Donne’s closer relatives, many of whom were executed or exiled for religious reasons. Donne was educated privately; however, there is no evidence to support the popular claim that he was taught by Jesuits. Donne’s mother married Dr. John Syminges, a wealthy widower with three children, a few months after Donne’s father died. Donne thus acquired a stepfather. Two more of his sisters, Mary and Katherine, died in 1581. Donne’s mother, who had lived in the Deanery after Donne became Dean of St. Paul’s, survived him, dying in 1632. In 1583, the 11-year-old Donne began studies at Hart Hall, now Hertford College, Oxford. After three years of studies there, Donne was admitted to the University of Cambridge, where he studied for another three years. However, Donne could not obtain a degree from either institution because of his Catholicism, since he refused to take the Oath of Supremacy required of graduates.

In 1591 Donne was accepted as a student at the Thavies Inn legal school, one of the Inns of Chancery in London. On 6 May 1592 he was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn, one of the Inns of Court. In 1593, five years after the defeat of the Spanish Armada and during the intermittent Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604), Queen Elizabeth issued the first English statute against sectarian dissent from the Church of England, titled “An Act for restraining Popish recusants”. It defined “Popish recusants” as those “convicted for not repairing to some Church, Chapel, or usual place of Common Prayer to hear Divine Service there, but forbearing the same contrary to the tenor of the laws and statutes heretofore made and provided in that behalf”. Donne’s brother Henry was also a university student prior to his arrest in 1593 for harbouring a Catholic priest, William Harrington, whom he betrayed under torture. Harrington was tortured on the rack, hanged until not quite dead, and then subjected to disembowelment. Henry Donne died in Newgate prison of bubonic plague, leading Donne to begin questioning his Catholic faith. During and after his education, Donne spent much of his considerable inheritance on women, literature, pastimes and travel.[6] Although no record details precisely where Donne travelled, he did cross Europe and later fought with the Earl of Essex and Sir Walter Raleigh against the Spanish at Cadiz (1596) and the Azores (1597), and witnessed the loss of the Spanish flagship, the San Felipe.

During the next four years, he fell in love with Egerton’s niece Anne More. They were married just before Christmas in 1601, against the wishes of both Egerton and George More, who was Lieutenant of the Tower and Anne’s father. This wedding ruined Donne’s career and earned him a short stay in Fleet Prison, along with Samuel Brooke, who married them, and the man who acted as a witness to the wedding. Donne was released when the marriage was proven valid, and he soon secured the release of the other two. Walton tells us that when Donne wrote to his wife to tell her about losing his post, he wrote after his name: John Donne, Anne Donne, Un-done. It was not until 1609 that Donne was reconciled with his father-in-law and received his wife’s dowry. After his release, Donne had to accept a retired country life in Pyrford, Surrey. Over the next few years, he scraped a meagre living as a lawyer, depending on his wife’s cousin Sir Francis Wolley to house him, his wife, and their children. Because Anne Donne bore a new baby almost every year, this was a very generous gesture. Though he practised law and may have worked as an assistant pamphleteer to Thomas Morton, Donne was in a constant state of financial insecurity, with a growing family to provide for.

Anne bore John twelve children in sixteen years of marriage (including two stillbirths—their eighth and then, in 1617, their last child); indeed, she spent most of her married life either pregnant or nursing. The ten surviving children were Constance, John, George, Francis, Lucy (named after Donne’s patroness Lucy, Countess of Bedford, her godmother), Bridget, Mary, Nicholas, Margaret, and Elizabeth. Three (Francis, Nicholas, and Mary) died before they were ten. In a state of despair that almost drove him to kill himself, Donne noted that the death of a child would mean one mouth fewer to feed, but he could not afford the burial expenses. During this time, Donne wrote, but did not publish, Biathanatos, his defence of suicide His wife died on 15 August 1617, five days after giving birth to their twelfth child, a still-born baby. Donne mourned her deeply, and wrote of his love and loss in his 17th Holy Sonnet.

In 1602 John Donne was elected as Member of Parliament for the constituency of Brackley, but this was not a paid position. Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, being succeeded by King James I of Scotland. The fashion for coterie poetry of the period gave Donne a means to seek patronage and many of his poems were written for wealthy friends or patrons, especially Sir Robert Drury (17th century MP) (1575–1615), who became Donne’s chief patron in 1610. Donne wrote the two Anniversaries, An Anatomy of the World (1611) and Of the Progress of the Soul (1612) for Drury. In 1610 and 1611 he wrote two anti-Catholic polemics: Pseudo-Martyr and Ignatius his Conclave. Although James was pleased with Donne’s work, he refused to reinstate him at court and instead urged him to take holy orders. At length, Donne acceded to the King’s wishes and in 1615 was ordained into the Church of England.

Donne was awarded an honorary doctorate in divinity from Cambridge in 1615 and became a Royal Chaplain in the same year, and was made a Reader of Divinity at Lincoln’s Inn in 1616, where he served in the chapel as minister from then until 1622. In 1618 he became chaplain to Viscount Doncaster, who was on an embassy to the princes of Germany. Donne did not return to England until 1620. In 1621 Donne was made Dean of St Paul’s, a leading (and well-paid) position in the Church of England and one he held until his death in 1631. During his period as Dean his daughter Lucy died, aged eighteen. In late November and early December 1623 he suffered a nearly fatal illness, thought to be either typhus or a combination of a cold followed by a period of fever. During his convalescence he wrote a series of meditations and prayers on health, pain, and sickness that were published as a book in 1624 under the title of Devotions upon Emergent Occasions. One of these meditations, Meditation XVII, later became well known for its phrases “No man is an Iland” (often modernised as “No man is an island”) and “…for whom the bell tolls”. In 1624 he became vicar of St Dunstan-in-the-West, and 1625 a prolocutor to Charles I. He earned a reputation as an eloquent preacher and 160 of his sermons have survived, including the famous Death’s Duel sermon delivered at the Palace of Whitehall before King Charles I in February 1631.

It is thought that Donne’s final illness was stomach cancer, although this has not been proven. He died on 31 March 1631 having written many poems, most of which were circulated in manuscript during his lifetime. Donne was buried in old St Paul’s Cathedral, where a memorial statue of him was erected (carved from a drawing of him in his shroud), with a Latin epigraph probably composed by himself. Donne’s monument survived the 1666 fire, and is on display in the present building.

Born

- January, 22, 1572

- United Kingdom

- London, England

Died

- March, 31, 1631

- United Kingdom

- London, England

Cemetery

- Saint Paul's Cathedral

- London, England

- United Kingdom