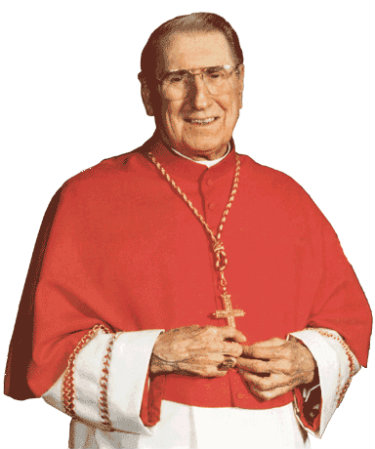

John Joseph O’Connor (John Joseph O'Connor)

O’Connor was born in Philadelphia, the fourth of five children of Thomas J. and Dorothy Magdalene (née Gomple) O’Connor (1886–1971), daughter of Gustave Gumpel, a kosher butcher and Jewish rabbi. In 2014, his sister Mary O’Connor Ward discovered through genealogical research that their mother was born Jewish and was baptized as a Roman Catholic at age 19. John’s parents were wed the following year. He attended public schools until his junior year of high school, when he enrolled in West Philadelphia Catholic High School for Boys. O’Connor then enrolled at St. Charles Borromeo Seminary, and after graduating from there he was ordained a priest for the Archdiocese of Philadelphia on December 15, 1945, by Hugh L. Lamb, then an auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese. He was initially assigned to teach at St. James High School in Chester, Pennsylvania. O’Connor joined the United States Navy in 1952 as a military chaplain during the Korean War, often entering combat zones in order to say Mass and to administer last rites to soldiers. He rose through the ranks to become a rear admiral and Chief of Chaplains of the Navy. During this period, he was made an Honorary Prelate of His Holiness, with the title of Right Reverend Monsignor, on October 27, 1966. O’Connor obtained a master’s degree in advanced ethics from Villanova University and in 1970 a doctorate in political science from Georgetown University, where he studied at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service and wrote his dissertation under future United Nations ambassador, Jeane Kirkpatrick.

On April 24, 1979, Pope John Paul II appointed O’Connor as auxiliary bishop of the Military Vicariate for the United States, subsequently reorganized as the Archdiocese for the Military Services in 1985, and titular bishop of Cursola. He was consecrated to the episcopate on May 27, 1979 at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome by John Paul himself, along with Cardinals Duraisamy Simon Lourdusamy and Eduardo Martínez Somalo as co-consecrators. On May 6, 1983, John Paul II named O’Connor Bishop of Scranton, and he was installed in that position on the following June 29. On January 26, 1984, after the death of Cardinal Terence Cooke three months earlier, O’Connor was appointed Archbishop of New York and administrator of the Military Vicariate of the United States, and installed on March 19. He was elevated to cardinal in the consistory of May 25, 1985, with the titulur church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Rome, the traditional one for the Archbishop of New York. As Archbishop, O’Connor skillfully brought to bear the power and prestige of his office to bear witness to traditional Catholic doctrine. Upon his death, the New York Times called O’Connor “a familiar and towering presence, a leader whose views and personality were forcefully injected into the great civic debates of his time, a man who considered himself a conciliator, but who never hesitated to be a combatant”, and one of the Catholic Church’s “most powerful symbols on moral and political issues.”

O’Connor believed in protecting all human life, from the unborn to convicts on death row. He was a forceful opponent of abortion, human cloning, capital punishment, human trafficking, and unjust war. Horrified by a visit to Dachau concentration camp, O’Connor was inspired to found a Roman Catholic religious institute dedicated to the sanctity of all human life to serve the unborn and dying. In 1991 his dream was realized in the Sisters of Life. He assailed what he called the “horror of euthanasia”, asking rhetorically, “What makes us think that permitted lawful suicide will not become obligated suicide?” In 2000, O’Connor called for a “major overhaul” of the punitive Rockefeller drug laws, which he believed produced “grave injustices”.

Despite his years spent as a Navy chaplain, O’Connor offered severe critiques of some United States military policies. In the 1980s, he condemned U.S. support for counterrevolutionary guerrilla forces in Central America, opposed the U.S.’s mining of the waters off Nicaragua, questioned spending on new weapons systems, and preached caution in regard to American military actions abroad. In 1998, he questioned whether the United States’ cruise missile strikes on Afghanistan and Sudan were morally justifiable. In 1999, during the Kosovo War, he used his weekly column in the archdiocesan newspaper, Catholic New York, to challenge repeatedly the morality of NATO’s bombing campaign of Yugoslavia, suggesting that it did not meet the Catholic Church’s criteria for a just war, and going so far as to ask, “Does the relentless bombing of Yugoslavia prove the power of the Western world or its weakness?” Three years before the 9/11 attacks on New York City, O’Connor insisted that the traditional just war principles must be applied to evaluate the morality of military responses to unconventional warfare and terrorism.

O’Connor’s father had been a union member, and O’Connor was also a passionate defender of organized labor and an advocate for the poor and the homeless. Early in his tenure, O’Connor set a pro-labor direction for the Archdiocese. During a strike in 1984 by 1199, the largest health care workers union in New York, O’Connor strongly criticized the League of Voluntary Hospitals, of which the Archdiocese was a member, for threatening to fire striking union members who refused to return to work, calling it “strikebreaking” and vowing that no Catholic hospital would do so. The following year, when a contract with 1199 still had not been reached, he threatened to break with the League and settle with the union unilaterally to reach an agreement “that gives justice to the workers”. In 1987, when the television broadcast employees union was on strike against NBC, a non-union crew from NBC appeared at the Cardinal’s residence to cover one of O’Connor’s press conferences. O’Connor declined to admit them, directing his secretary to “tell them they’re not invited.” Following his death, SEIU 1199, published a 12-page tribute to O’Connor, calling him “the patron saint of working people” and describing his support for low-wage and other workers and his efforts in helping limousine drivers unionize, helping end the strike at The Daily News in 1990, and pushing for fringe benefits for minimum-wage home health care workers.

O’Connor played an active role in Catholic-Jewish relations. He strongly denounced anti-Semitism, declaring that one “cannot be a faithful Christian and an anti-Semite. They are incompatible, because anti-Semitism is a sin.” He wrote an apology to Jewish leaders in New York for past harm done to the Jewish community. O’Connor criticized Swiss banks’ failure to compensate victims of the Holocaust, which he called “a human rights issue, an issue of the human race.” Even when disagreeing with him over political questions, Jewish leaders acknowledged that O’Connor was “a friend, a powerful voice against anti-Semitism”. The Jewish Council for Public Affairs called him, “a true friend and champion of Catholic-Jewish relations [and] a humanitarian who used the power of his pulpit to advocate for disadvantaged people throughout the world and in his own community.” Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel called O’Connor, “a good Christian” and a man “who understands our pain.”

The Cardinal opposed condom distribution as an AIDS-prevention measure, viewing it as being contrary to the Church’s teaching that contraception is immoral and its use a sin. O’Connor rejected the argument that condoms distributed to gay men are not contraceptives. O’Connor’s response was that using an “evil act” was not justified by good intentions, and that the Church should not be seen as encouraging sinful acts among others (other fertile heterosexual couples who might wrongly interpret his narrow support as license for their own contraception). He also claimed that sexual abstinence is a sure way to prevent infection, claiming condoms were only 50% effective against HIV transmission. HIV activist group ACT UP was appalled by the Cardinal’s apparent opinion that it was sinful for an HIV positive person to use a condom to prevent transmission of HIV to his HIV negative partner, an opinion they believe would translate directly into more deaths. This caused many of the confrontations between the group and the Cardinal. Early on in the AIDS epidemic, he approved the opening of a specialized AIDS unit to provide medical care for the sick and dying in the former St. Clare’s Hospital in Manhattan, the first of its kind in the state. He often nurtured and ministered to dying AIDS patients, many of whom were homosexual. Even though he condemned homosexual acts—some members of ACT UP had protested in front of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in his absence, to protest, holding placards such as “Cardinal O’Connor Loves Gay People…If They Are Dying of AIDS”—) he would not allow his moral differences to interfere with ministering to them.

In 1987, O’Connor was appointed to President Ronald Reagan’s President’s Commission on the HIV Epidemic, also known as the Watkins Commission, serving alongside 12 other members, few of whom were AIDS experts, including James D. Watkins, Richard DeVos, and Penny Pullen. The Commission was initially controversial among HIV researchers and activists as lacking expertise on the disease and as being in disarray. The Watkins Commission surprised many of its critics, however, by issuing a final report in 1988 that lent conservative support for antibias laws to protect HIV-positive people, on-demand treatment for drug addicts, and the speeding of AIDS-related research. The New York Times praised the Commission’s “remarkable strides” and its proposed $2 billion campaign against AIDS among drug addicts. The Watkins Commission’s recommendations were similar to the recommendations subsequently made by a committee of HIV experts appointed by the National Academy of Sciences. On December 10, 1989, 4,500 members of ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) and WHAM (Women’s Health Action and Mobilization) held a demonstration at Saint Patricks Cathedral to voice their opposition to the Cardinals to AIDS education, the distribution of condoms in public schools and his position on abortion, during which 43 people were arrested inside the cathedral. At the time it was the largest demonstration against the Catholic church in history and remained so until Pope Benedict XVI’s visit in 2010 to the UK caused protests by approximately 20,000 people.

When O’Connor reached the retirement age for bishops of 75 in January 1995, he submitted his resignation to Pope John Paul II as required by Church law, but the Pope did not accept it. He was diagnosed in 1999 as having a brain tumor, from which he eventually died. He continued to serve as Archbishop of New York until his death. O’Connor died in the Archbishop’s residence on May 3, 2000 and was interred in the crypt beneath the main altar of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan, President Bill Clinton and First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, former President George H.W. Bush, Texas Governor George W. Bush, New York Governor George Pataki and New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani were among the dignitaries who attended his funeral, which was presided over by the Cardinal Secretary of State Angelo Sodano. The eulogy was delivered by Cardinal William W. Baum.

Born

- January, 15, 1920

- USA

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Died

- May, 03, 2000

- USA

- New York, New York

Cause of Death

- brain tumor

Cemetery

- Saint Patricks Cathedral

- Manhattan, New York

- USA