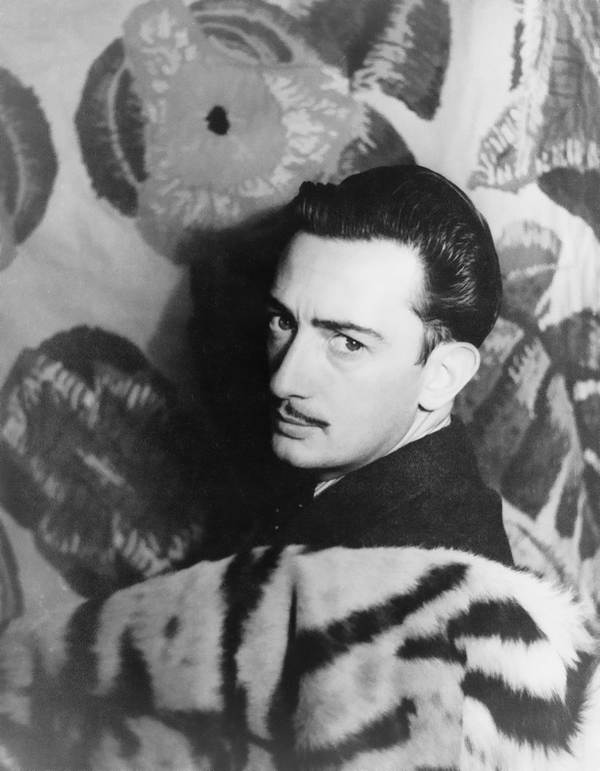

Salvador Dali (Salvador Dali)

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech was born on May 11, 1904, at 8:45 am GMT in the town of Figueres, in the Empordà region, close to the French border in Catalonia, Spain. Dalí’s older brother, also named Salvador (born October 12, 1901), had died of gastroenteritis nine months earlier, on August 1, 1903. His father, Salvador Dalí i Cusí, was a middle-class lawyer and notary whose strict disciplinary approach was tempered by his wife, Felipa Domenech Ferrés, who encouraged her son’s artistic endeavors. When he was five, Dalí was taken to his brother’s grave and told by his parents that he was his brother’s reincarnation, a concept which he came to believe. Of his brother, Dalí said, “…[we] resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections.” He “was probably a first version of myself but conceived too much in the absolute.” Images of his long-dead brother would reappear embedded in his later works, including Portrait of My Dead Brother (1963). Dalí also had a sister, Ana María, who was three years younger. In 1949, she published a book about her brother, Dalí As Seen By His Sister. His childhood friends included future FC Barcelona footballers Sagibarba and Josep Samitier. During holidays at the Catalan resort of Cadaqués, the trio played football together. Dalí attended drawing school. In 1916, Dalí also discovered modern painting on a summer vacation trip to Cadaqués with the family of Ramon Pichot, a local artist who made regular trips to Paris. The next year, Dalí’s father organized an exhibition of his charcoal drawings in their family home. He had his first public exhibition at the Municipal Theater in Figueres in 1919. In February 1921, Dalí’s mother died of breast cancer. Dalí was 16 years old; he later said his mother’s death “was the greatest blow I had experienced in my life. I worshipped her… I could not resign myself to the loss of a being on whom I counted to make invisible the unavoidable blemishes of my soul.” After her death, Dalí’s father married his deceased wife’s sister. Dalí did not resent this marriage, because he had a great love and respect for his aunt.

In 1922, Dalí moved into the Residencia de Estudiantes (Students’ Residence) in Madrid and studied at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. A lean 1.72 m (5 ft. 7¾ in.) tall, Dalí already drew attention as an eccentric and dandy. He had long hair and sideburns, coat, stockings, and knee-breeches in the style of English aesthetes of the late 19th century. At the Residencia, he became close friends with (among others) Pepín Bello, Luis Buñuel, and Federico García Lorca. The friendship with Lorca had a strong element of mutual passion, but Dalí rejected the poet’s sexual advances.

However it was his paintings, in which he experimented with Cubism, that earned him the most attention from his fellow students. His only information on Cubist art came from magazine articles and a catalog given to him by Pichot, since there were no Cubist artists in Madrid at the time. In 1924, the still-unknown Salvador Dalí illustrated a book for the first time. It was a publication of the Catalan poem Les bruixes de Llers (“The Witches of Llers”) by his friend and schoolmate, poet Carles Fages de Climent. Dalí also experimented with Dada, which influenced his work throughout his life. Dalí was expelled from the Academia in 1926, shortly before his final exams when he was accused of starting an unrest. His mastery of painting skills was evidenced by his realistic The Basket of Bread, painted in 1926. That same year, he made his first visit to Paris, where he met Pablo Picasso, whom the young Dalí revered. Picasso had already heard favorable reports about Dalí from Joan Miró. As he developed his own style over the next few years, Dalí made a number of works heavily influenced by Picasso and Miró.

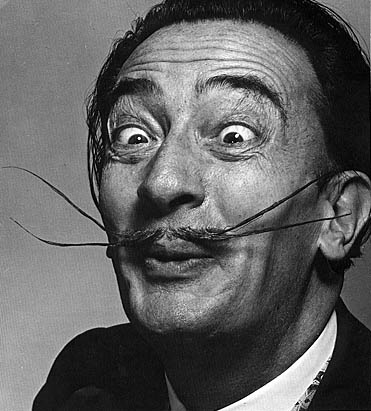

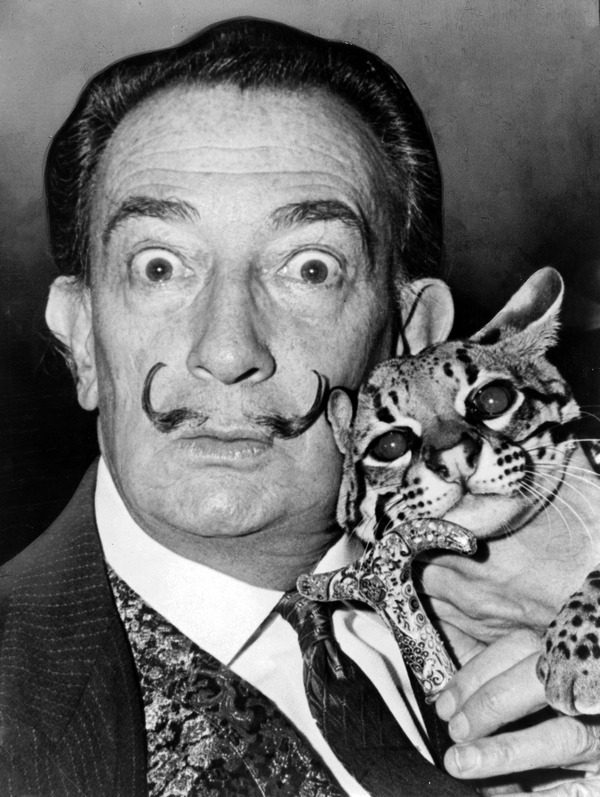

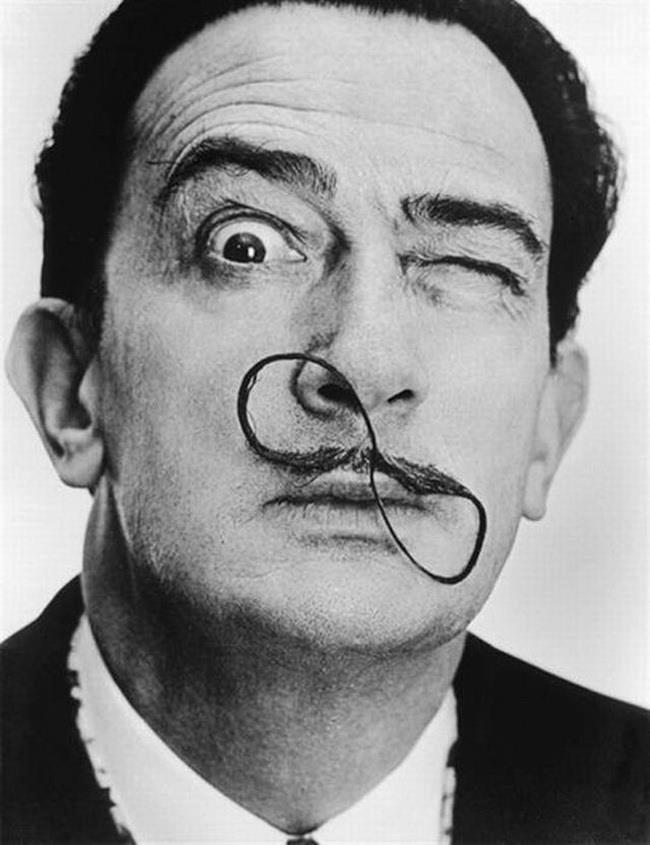

Some trends in Dalí’s work that would continue throughout his life were already evident in the 1920s. Dalí devoured influences from many styles of art, ranging from the most academically classic, to the most cutting-edge avant garde. His classical influences included Raphael, Bronzino, Francisco de Zurbarán, Vermeer, and Velázquez. He used both classical and modernist techniques, sometimes in separate works, and sometimes combined. Exhibitions of his works in Barcelona attracted much attention along with mixtures of praise and puzzled debate from critics. Dalí grew a flamboyant moustache, influenced by 17th-century Spanish master painter Diego Velázquez. The moustache became an iconic trademark of his appearance for the rest of his life.

In 1929, Dalí collaborated with surrealist film director Luis Buñuel on the short film Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog). His main contribution was to help Buñuel write the script for the film. Dalí later claimed to have also played a significant role in the filming of the project, but this is not substantiated by contemporary accounts. Also, in August 1929, Dalí met his lifelong and primary muse, inspiration, and future wife Gala, born Elena Ivanovna Diakonova. She was a Russian immigrant ten years his senior, who at that time was married to surrealist poet Paul Éluard. In the same year, Dalí had important professional exhibitions and officially joined the Surrealist group in the Montparnasse quarter of Paris. His work had already been heavily influenced by surrealism for two years. The Surrealists hailed what Dalí called his paranoiac-critical method of accessing the subconscious for greater artistic creativity.

Meanwhile, Dalí’s relationship with his father was close to rupture. Don Salvador Dalí y Cusi strongly disapproved of his son’s romance with Gala, and saw his connection to the Surrealists as a bad influence on his morals. The final straw was when Don Salvador read in a Barcelona newspaper that his son had recently exhibited in Paris a drawing of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Christ, with a provocative inscription: “Sometimes, I spit for fun on my mother’s portrait”. Outraged, Don Salvador demanded that his son recant publicly. Dalí refused, perhaps out of fear of expulsion from the Surrealist group, and was violently thrown out of his paternal home on December 28, 1929. His father told him that he would be disinherited, and that he should never set foot in Cadaqués again. The following summer, Dalí and Gala rented a small fisherman’s cabin in a nearby bay at Port Lligat. He bought the place, and over the years enlarged it, gradually building his much beloved villa by the sea. Dalí’s father would eventually relent and come to accept his son’s companion.

In 1931, Dalí painted one of his most famous works, The Persistence of Memory, which introduced a surrealistic image of soft, melting pocket watches. The general interpretation of the work is that the soft watches are a rejection of the assumption that time is rigid or deterministic. This idea is supported by other images in the work, such as the wide expanding landscape, and other limp watches shown being devoured by ants. Dalí and Gala, having lived together since 1929, were married in 1934 in a semi-secret civil ceremony. They later remarried in a Catholic ceremony in 1958. In addition to inspiring many artworks throughout her life, Gala would act as Dalí’s business manager, supporting their extravagant lifestyle while adeptly steering clear of insolvency. Gala seemed to tolerate Dalí’s dalliances with younger muses, secure in her own position as his primary relationship. Dalí continued to paint her as they both aged, producing sympathetic and adoring images of his muse. The “tense, complex and ambiguous relationship” lasting over 50 years would later become the subject of an opera Jo, Dalí (I, Dalí) by Catalan composer Xavier Benguerel. Dalí was introduced to the United States by art dealer Julien Levy in 1934. The exhibition in New York of Dalí’s works, including Persistence of Memory, created an immediate sensation.Social Register listees feted him at a specially organized “Dalí Ball”. He showed up wearing a glass case on his chest, which contained a brassiere. In that year, Dalí and Gala also attended a masquerade party in New York, hosted for them by heiress Caresse Crosby. For their costumes, they dressed as the Lindbergh baby and his kidnapper. The resulting uproar in the press was so great that Dalí apologized. When he returned to Paris, the Surrealists confronted him about his apology for a surrealist act.

While the majority of the Surrealist artists had become increasingly associated with leftist politics, Dalí maintained an ambiguous position on the subject of the proper relationship between politics and art. Leading surrealist André Breton accused Dalí of defending the “new” and “irrational” in “the Hitler phenomenon”, but Dalí quickly rejected this claim, saying, “I am Hitlerian neither in fact nor intention”. Dalí insisted that surrealism could exist in an apolitical context and refused to explicitly denounce fascism. Among other factors, this had landed him in trouble with his colleagues. Later in 1934, Dalí was subjected to a “trial”, in which he was formally expelled from the Surrealist group. To this, Dalí retorted, “I myself am surrealism”. In 1936, Dalí took part in the London International Surrealist Exhibition. His lecture, titled Fantômes paranoiaques authentiques, was delivered while wearing a deep-sea diving suit and helmet. He had arrived carrying a billiard cue and leading a pair of Russian wolfhounds, and had to have the helmet unscrewed as he gasped for breath. He commented that “I just wanted to show that I was ‘plunging deeply’ into the human mind.”

Also in 1936, at the premiere screening of Joseph Cornell’s film Rose Hobart at Julien Levy’s gallery in New York City, Dalí became famous for another incident. Levy’s program of short surrealist films was timed to take place at the same time as the first surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, featuring Dalí’s work. Dalí was in the audience at the screening, but halfway through the film, he knocked over the projector in a rage. “My idea for a film is exactly that, and I was going to propose it to someone who would pay to have it made,” he said. “I never wrote it down or told anyone, but it is as if he had stolen it”. Other versions of Dalí’s accusation tend to the more poetic: “He stole it from my subconscious!” or even “He stole my dreams!”

In this period, Dalí’s main patron in London was the very wealthy Edward James. He had helped Dalí emerge into the art world by purchasing many works and by supporting him financially for two years. They also collaborated on two of the most enduring icons of the Surrealist movement: the Lobster Telephone and the Mae West Lips Sofa. Meanwhile, Spain was going through a civil war (1936-1939), with many artists taking a side or going into exile. In 1938, Dalí met Sigmund Freud thanks to Stefan Zweig. Later, in September 1938, Salvador Dalí was invited by Gabrielle Coco Chanel to her house “La Pausa” in Roquebrune on the French Riviera. There he painted numerous paintings he later exhibited at Julien Levy Gallery in New York. At the end of the 20th century, “La Pausa” was partially replicated at the Dallas Museum of Art to welcome the Reeves collection and part of Chanel’s original furniture for the house.

Also in 1938, Dalí unveiled Rainy Taxi, a three-dimensional artwork, consisting of an actual automobile with two mannequin occupants. The piece was first displayed at the Galerie Beaux-Arts in Paris at the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme, organised by André Breton and Paul Eluard. The Exposition was designed by artist Marcel Duchamp, who also served as host. At the 1939 New York World’s Fair, Dalí debuted his Dream of Venus surrealist pavilion, located in the Amusements Area of the exposition. It featured bizarre sculptures, statues, and live nude models in “costumes” made of fresh seafood, an event photographed by Horst P. Horst, George Platt Lynes, and Murray Korman. Like most attractions in the Amusements Area, an admission fee was charged.

In 1939, André Breton coined the derogatory nickname “Avida Dollars”, an anagram for “Salvador Dalí”, which may be more or less translated as “eager for dollars”. This was a derisive reference to the increasing commercialization of Dalí’s work, and the perception that Dalí sought self-aggrandizement through fame and fortune. Some surrealists henceforth spoke of Dalí in the past tense, as if he were dead. The Surrealist movement and various members thereof (such as Ted Joans) would continue to issue extremely harsh polemics against Dalí until the time of his death, and beyond.

In 1940, as World War II tore through Europe, Dalí and Gala retreated to the United States, where they lived for eight years. They were able to escape because on June 20, 1940, they were issued visas by Aristides de Sousa Mendes, Portuguese consul in Bordeaux, France. Dalí’s arrival in New York was one of the catalysts in the development of that city as a world art center in the post-War years. Salvador and Gala Dalí crossed into Portugal and subsequently sailed on the Excambion from Lisbon to New York in August 1940. After the move, Dalí returned to the practice of Catholicism. “During this period, Dalí never stopped writing”, wrote Robert and Nicolas Descharnes. In 1941, Dalí drafted a film scenario for Jean Gabin called Moontide. In 1942, he published his autobiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. He wrote catalogs for his exhibitions, such as that at the Knoedler Gallery in New York in 1943. Therein he attacked some often-used surrealist techniques by proclaiming, “Surrealism will at least have served to give experimental proof that total sterility and attempts at automatizations have gone too far and have led to a totalitarian system. … Today’s laziness and the total lack of technique have reached their paroxysm in the psychological signification of the current use of the college” (collage). He also wrote a novel, published in 1944, about a fashion salon for automobiles. This resulted in a drawing by Edwin Cox in The Miami Herald, depicting Dalí dressing an automobile in an evening gown.

Also, in The Secret Life Dalí suggested that he had split with Luis Buñuel because the latter was a Communist and an atheist. Buñuel was fired (or resigned) from his position at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), supposedly after Cardinal Spellman of New York went to see Iris Barry, head of the film department at MOMA. Buñuel then went back to Hollywood where he worked in the dubbing department of Warner Brothers from 1942 to 1946. In his 1982 autobiography Mon Dernier soupir (My Last Sigh, 1983), Buñuel wrote that, over the years, he had rejected Dalí’s attempts at reconciliation. An Italian friar, Gabriele Maria Berardi, claimed to have performed an exorcism on Dalí while he was in France in 1947. In 2005, a sculpture of Christ on the Cross was discovered in the friar’s estate. It had been claimed that Dalí gave this work to his exorcist out of gratitude, and two Spanish art experts confirmed that there were adequate stylistic reasons to believe the sculpture was made by Dalí.

From 1949 onwards, Dalí spent his remaining years back in Spain. His acceptance and embracing of Franco’s dictatorship were strongly disapproved of by other Spanish artists and intellectuals who stayed in exile. In 1959, André Breton organized an exhibit called Homage to Surrealism, celebrating the fortieth anniversary of Surrealism, which contained works by Dalí,Joan Miró, Enrique Tábara, and Eugenio Granell. Breton vehemently fought against the inclusion of Dalí’s Sistine Madonna in the International Surrealism Exhibition in New York the following year.

Late in his career, Dalí did not confine himself to painting, but experimented with many unusual or novel media and processes: he made bulletist works. Many of his works incorporated optical illusions, negative space, visual puns, and trompe l’oeil visual effects. He also experimented with pointillism, enlarged half-tone dot grids (which Roy Lichtenstein would later use), andstereoscopic images. He was among the first artists to employ holography in an artistic manner. In his later years, young artists such as Andy Warhol proclaimed Dalí an important influence on pop art. Dalí also had a keen interest in natural science and mathematics. This is manifested in several of his paintings, notably from the 1950s, in which he painted his subjects as composed of rhinoceros horn shapes. According to Dalí, the rhinoceros horn signifies divine geometry because it grows in a logarithmic spiral. He also linked the rhinoceros to themes of chastity and to the Virgin Mary. Dalí was also fascinated by DNA and the tesseract (a 4-dimensional cube); an unfolding of a hypercube is featured in the painting Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus). At some point, Dalí had a glass floor installed in a room near his studio. He made extensive use of it to study foreshortening, both from above and from below, incorporating dramatic perspectives of figures and objects into his paintings. He also delighted in using the room for entertaining guests and visitors to his house and studio.

Dalí’s post–World War II period bore the hallmarks of technical virtuosity and an intensifying interest in optical effects, science, and religion. He became an increasingly devout Catholic, while at the same time he had been inspired by the shock of Hiroshima and the dawning of the “atomic age”. Therefore Dalí labeled this period “Nuclear Mysticism.” In paintings such as The Madonna of Port Lligat (first version) (1949) and Corpus Hypercubus (1954), Dalí sought to synthesize Christian iconography with images of material disintegration inspired by nuclear physics. His Nuclear Mysticism works included such notable pieces as La Gare de Perpignan (1965) and The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968–70). In 1960, Dalí began work on his Teatro Museo (Dalí Theatre and Museum) in his home town of Figueres; it was his largest single project and the main focus of his energy through 1974. He continued to make additions through the mid-1980s.

In 1968, Dalí filmed a humorous television advertisement for Lanvin chocolates. In this, he proclaims in French “Je suis fou du chocolat Lanvin!” (‘I’m crazy about Lanvin chocolate’) while biting a morsel causing him to become crosseyed and his moustache to swivel upwards. In 1969, he designed the Chupa Chups logo in addition to facilitating the design of the advertising campaign for the 1969 Eurovision Song Contest and creating a large on-stage metal sculpture that stood at the Teatro Real in Madrid. In the television programme Dirty Dalí: A Private View broadcast on Channel 4 on June 3, 2007, art critic Brian Sewell described his acquaintance with Dalí in the late 1960s, which included lying down in the fetal position without trousers in the armpit of a figure of Christ and masturbating for Dalí, who pretended to take photos while fumbling in his own trousers.

In 1980 at age 76, Dalí’s health took a catastrophic turn. His right hand trembled terribly, with Parkinson-like symptoms. His near-senile wife, Gala Dalí, allegedly had been dosing him with a dangerous cocktail of unprescribed medicine that damaged his nervous system, thus causing an untimely end to his artistic capacity. In 1982, King Juan Carlos bestowed on Dalí the title of Marqués de Dalí de Púbol (Marquis of Dalí de Púbol) in the nobility of Spain, hereby referring to Púbol, the place where he lived. The title was in first instance hereditary, but on request of Dalí changed to life only in 1983. To show his gratitude for this, Dalí later gave the king a drawing (Head of Europa, which would turn out to be Dalí’s final drawing) after the king visited him on his deathbed. Gala died on June 10, 1982, at the age of 87. After Gala’s death, Dalí lost much of his will to live. He deliberately dehydrated himself, possibly as a suicide attempt, with claims stating he had tried to put himself into a state of suspended animation as he had read that some microorganisms could do. He moved from Figueres to the castle in Púbol, which he had bought for Gala and had been the site of her death.

In 1984, a fire broke out in his bedroom under unclear circumstances. It was possibly a suicide attempt by Dalí, or possibly simple negligence by his staff. Dalí was rescued by friend and collaborator Robert Descharnes and returned to Figueres, where a group of his friends, patrons, and fellow artists saw to it that he was comfortable living in his Theater-Museum in his final years. There have been allegations that Dalí was forced by his guardians to sign blank canvases that would later, even after his death, be used in forgeries and sold as originals. As a result, art dealers tend to be wary of late works attributed to Dalí. In November 1988, Dalí entered the hospital with heart failure; a pacemaker had already been implanted previously. On December 5, 1988, he was visited by King Juan Carlos, who confessed that he had always been a serious devotee of Dalí.

On January 23, 1989, while his favorite record of Tristan and Isolde played, he died of heart failure at Figueres at the age of 84. He is buried in the crypt of his Teatro Museo in Figueres. The location is across the street from the church of Sant Pere, where he had his baptism, first communion, and funeral, and is only three blocks from the house where he was born. The Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation currently serves as his official estate. The US copyright representative for the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation is the Artists Rights Society. In 2002, the Society made the news when they asked Google to remove a customized version of its logo put up to commemorate Dalí, alleging that portions of specific artworks under their protection had been used without permission. Google complied with the request, but denied that there was any copyright violation.

Born

- May, 11, 1904

- Figueres, Spain

Died

- January, 23, 1989

- Figueres, Spain

Cemetery

- Salvador Dali Museum

- Cataluna, Spain